Ed Smith Stadium in springtime should be hosting baseball tournaments. Instead, the venue in early May served as a distribution center for All Faiths Food Bank. A line-up of vehicles drove to the stadium and popped open trunks before boxes of free food could be shoved in and the cars sent on their way, with never so much as a handshake shared.

That's the coldness of social distancing in the coronavirus era, merged with the demand and desperation of a sudden hunger crisis. It’s also the fruits of a massive campaign to feed the region by a philanthropic organization facing a dilemma like no other before it. There’s no hearty embraces, but there’s compassion loaded with every delivery. And there’s work—hard work—as the food bank tackles a crisis with no end in sight. Serving communities in crisis isn’t new for food banks. Poverty. Hurricanes. Broken supply lines. There’s a playbook at All Faiths Food Bank to navigate emergencies, catastrophe and run-of-the-mill misery. But nothing on paper or in Executive Director Sandra Frank’s years of experience quite prepared her for the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We came into this with disaster response. This is what we do,” she said. “Whether it’s the fires in California or natural disasters, we are accustomed to those shutdowns that occur. This isn’t that.”

Like many nonprofits and government agencies, the food bank must serve a community economically devastated by a loss of jobs unlike anything recorded since the Great Depression. It must respond without the help of volunteers, sent home for fear that gathering them together would risk the spread of a novel coronavirus more contagious than anything threatening Florida in a century. And the work must be done while donations from individuals and corporate partners screech to a sudden and unexpected stop. But like many philanthropic organizations feeding the region, work won’t stop while need still exists. With a public health crisis, economic chaos and social anxieties storming the region at once, those dedicated with keeping the hungriest mouths fed are seeking out creative ways to continue serving.

Through the early months of 2020, the coronavirus seemed a frightening but distant threat. A variation of SARS, the spread of sickness delivered somewhat familiar pictures of people walking the streets of foreign cities, first in China, then Italy, but eventually California and New York. Then Florida’s first case arrived and with startling closeness— reported from the Sarasota-Bradenton area. Doctors Hospital of Sarasota on March 1 revealed through a memo to patients and staff that an individual had been diagnosed with the coronavirus and remained in isolation there. The Florida Department of Health revealed the individual to be a Manatee County resident with no significant travel history, evidence of “community spread” for a virus not yet believed to be in the state.

As of May 18, Florida health officials reported 88 Manatee County residents had tested positive for COVID-19 and 533 in Sarasota had as well. A total of 145 individuals died from the disease. While the state has ramped up testing, including with a major drive-through site at University Town Center, the novel coronavirus has continued to spread even in the midst of an unprecedented economic shutdown that forced many companies to furlough or lay-off staff. The state of Florida for most of April issued a statewide stay-at-home order closing down businesses deemed nonessential, including many hotels, as local government closed down beaches. A ban on elective surgeries ironically sent economic woe into the health care industry. Restaurants cut staff to bare bones needed in order to maintain only take-out service. Meanwhile, Florida’s unemployment system crushed under the weight of millions of claims over just a matter of weeks, and with the turmoil, the range of people now classified as needy immediately became redefined.

At a dropoff point for donations to volunteers for Meals on Wheels of Sarasota don’t shake hands with the generous altruists coming to feed the hungry. Instead, they call through car windows to simply pop the trunk. Cardboard containers of food get wiped down before these givers of goods drive off, all in an effort to limit human contact and proximity.

For Robert Thomas, a 61-year-old living on his own in Sarasota, the meals are a lifeline to the other world. On a May morning, he raved about the chicken salad with a pear desert delivered to his door. The day before, he enjoyed warm roast beef. “I wouldn’t mind some mixed vegetables,” he said. But he’s happy to get this food. A former woodworker who lost a leg in a motorcycling accident years ago, he went on disability when arthritis forced him into retirement. He’s had his one knee replaced, and three months ago had an emergency surgery to replace a shoulder as well.

He’s had to carefully schedule visits to the hospital during a difficult recovery that, as it happens, he must endure in the midst of a pandemic. He’s received disability and food stamps, but those require trips to the grocery store. He used to strap on an artificial leg and ride there three times a week to buy food, but now, doesn’t want to venture frequently into the crowded supermarket. With Meals on Wheels of Sarasota bringing a lunch each day, he doesn’t have to risk the trip as often, and this is food he won’t need to cook. “It’s something I look forward to,” he said. “Now I don’t have to deal with this on my own.”

Marjorie Broughton, executive director for Meals on Wheels Sarasota, said demand for food delivered to individuals’ homes has grown dramatically since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. The operation’s changes have been challenging, but it’s became apparent quickly, the need for Meals on Wheels has grown greater than ever. Fortunately, the modus operandi for the organization in many ways seems tailored for the era of social distancing. Volunteers bring food to the homes of those without transportation or with underlying health conditions, and they can drop off meals without invading the six-foot personal space bubble that has come now to surround every citizen of the world.

While the organization typically focuses aid to seniors, volunteers now deliver packages to feed whole families. The organization expanded its reach to Nokomis and works its staff longer hours in the day as more apply for help.

The Sarasota group increased the number of meals it makes each day from about 500 to as many as 750, and packages get deployed seven days a week.

“We’re expecting to make about 80,000 more meals this year,” she said. “In one particular day, we picked up 100 new people,” Broughton recalls.

And there’s similar stories at operations around the country. The Food Bank of Manatee and Meals On Wheels Plus Manatee have worked closely together to deliver 128,000 meals over a span of eight weeks through its Food4Families Program. The Bradenton-based food bank alone saw a spike of 25,000 families a week. And while seniors over age 60, a demographic at particular risk of dying from COVID-19, remains the target market, the economic need in the area simply reaches across all demographics. The organization has swollen its volunteer ranks to more than 1,000, up from 750 pre-pandemic.

The particular challenges of working in a pandemic haven’t made it any easier to serve the tremendous demand on the region’s food providers. The way people rally volunteers, divvy up goods and even just accept donations has utterly transformed. Because the novel coronavirus at the heart of the pandemic spreads so easily in groups, by air and on surfaces, it puts new pressure on every step of the process on handling and delivering food.

For Jim Foubister, the chaplain for One Christ Won City, his missionary service always relied on outreach to churches in south Sarasota County. He’s normally at a different church each Sunday, speaking with one of maybe two dozen congregations and recruiting volunteers to serve. With the pandemic underway, the nonprofit launched the Feed Venice initiative to handle the growing need, but Foubister simultaneously found himself with a new recruiting and communication challenge.

“We put on hold any gatherings,” he said. “We have been remotely meeting with pastors and leaders in the city.” Some churches may still hold video services but gatherings on Sunday have largely come to a halt— the same as concerts, school assemblies and large dinner parties. But the ministry since its launch in 2009 has tapped into larger networks of support as well. Foubister works with Serve Florida, which offers connections to food banks statewide. That’s helped make up for any blow to normal infrastructure during a moment when Foubister hopes to ramp up the good of a hunger initiative.

But there’s other partners who normally lift the mission but who have been dealt their own blow by COVID-19. The postal service normally holds food drives annually to help feeding efforts, including the work at One Christ Won City, but the random drop of food goods in mailboxes this year couldn’t be done.

“We were forced to come to the realization the post office would not collect this year,” he said. “That’s 60,000 pounds of food that will not be available to feed the children through the summer. “Similarly, drives conducted at schools or by youth groups in the area all evaporated as schools shut down for most of the spring semester.

Frank shared that one of All Faiths’ chief source of supplies is normally the surplus inventory from groceries like Publix and Whole Foods. The products that don’t sell at major markets make up a significant portion of shelf space in the food bank. But with supply chain disruptions and greater demand on supermarkets as consumers cook and hoard more, it’s hard enough to keep aisles stocked for customers paying full price, much less at the charity taking the remaining surplus.

Broughton noted that in the food industry all goods get delivered in cardboard boxes that often will be recycled and reused until they fall apart. Right now, containers can’t be repacked without being completely sanitized, easier said than done with perishable containers. Meals On Wheels must use fogger disinfectant to make sure rooms full of containers stay virus-free.

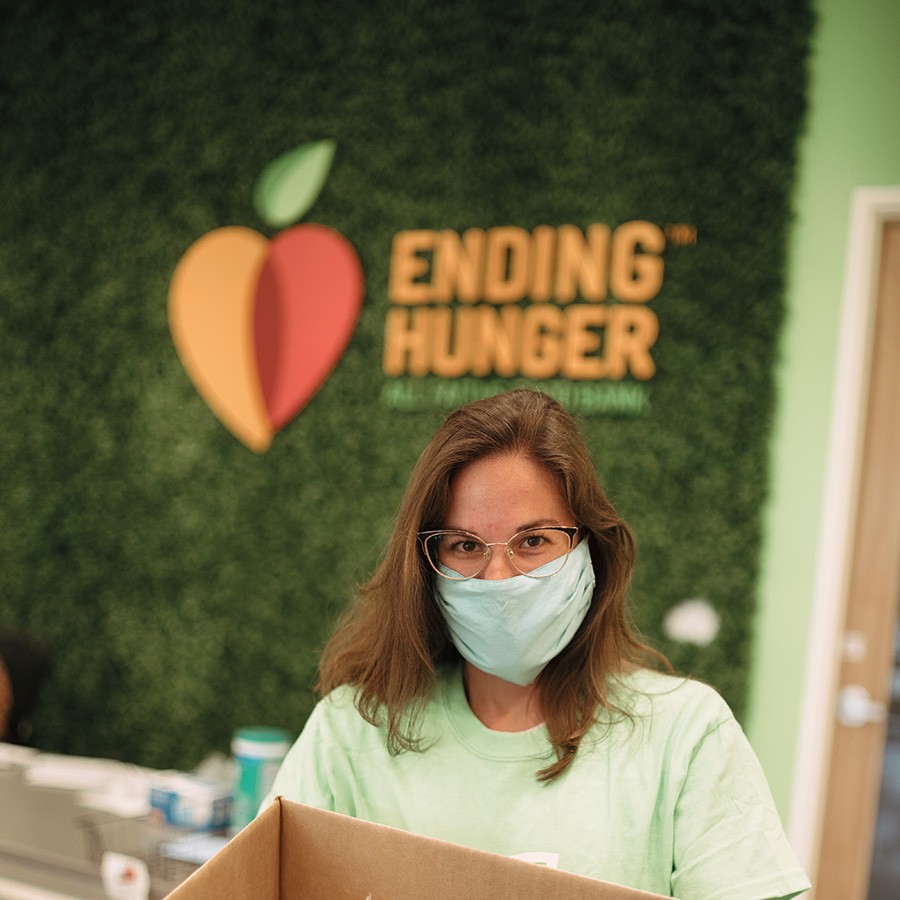

It’s all changing the foundational functions that keep food providers going. All Faiths for two consecutive weekends in May held drive-though distribution events, serving roughly 4,600 vehicles each time. In the new CoolToday Park and Ed Smith Stadium, facilities left largely unused after Major League Baseball canceled spring training this year, staffers for the organization loaded food into trunks while the National Guard helped enforce social distancing.

And then there's the societal mechanisms that quietly deliver food to children in need without much notice all year long, but whose daily interactions with children has been completely shut down. The public school system delivers education to all income strata of children in the community. But the cafeterias around the county serve a mission beyond that. The school year brings for many families access to cheap, or free, food for their children. Backpack programs often mean those students come home with goods for the entire family.

On March 13, the Florida Board of Education made the startling and unprecedented recommendation for all schools in the state to close. Districts already on Spring Break extended vacation for another week, and any district not yet on holiday closed down immediately. Remote learning systems were deployed over the course of two weeks so teachers could continue remote instruction for a period everyone hoped was temporary. But when Gov. Ron DeSantis announced a phased plan for reopening business in Florida, he said distance learning would need to continue through the end of the school year. There was no way, he said, to return instruction to classrooms knowing many families would not feel safe returning children into crowded schools.

And what of school lunch programs? Kelsey Whealy, spokesperson for the Sarasota County School District, said leaders quickly decided the food in school refrigerators could not be left to rot. The district began mass distribution of food for all students under the age of 18, beginning on March 23, making sure even if learning was to take place at home, students could still receive food for as long as necessary. But with social distancing and staffing demands, officials quickly rebuilt the infrastructure for putting food on students’ plates.

“We started with daily distributions but in an effort to serve our families more efficiently, and keep our staff and community healthy during the COVID-19 pandemic, we condensed our daily meal distributions for students, at all school distribution sites, to only one day a week starting on Thursday, April 9,” she said. “We now distribute a week’s worth of food to all children 18 and under every Friday at our select school sites.”

Schools still have to keep track of allergies and other factors, requiring options be made available. But the demand has been overwhelming, with six elementary and two high schools serving a steady stream of students through drive-through sites. The district decided in May to go ahead and keep serving food until the end of the summer. It will depend on what a return to school in the fall looks like where the food program goes from there. That’s helped to make sure not just that students won’t learn on an empty stomach, but that families won’t have the added stress of losing a lunch program on top of being laid-off from a job.

The Sarasota community has benefitted, as it so often does, from the generosity of philanthropists living around the Gulf Coast. The Community Foundation of Sarasota County held its annual Giving Challenge on schedule this year, embracing the fact a world in isolation could still convene digitally for a donor event. In a sign of shifting priorities amid the global crisis, All Faiths Food Bank ended up as the organization receiving the most gifts. Individuals gave $369,535 in a 24-hour period, money matched with another $252,402 from The Patterson Foundation. Meals on Wheels Plus of Manatee came in second, with $205,095 in donations and another $90,125 in matching funds. In a competition where the blue ribbon usually goes to organizations sheltering cats or creating stage shows, the sight of two food-based organizations atop the leaderboards hinted at exactly the level of need and the overwhelming community sense that priorities, for now, must change.

Roxie Jerde, president and CEO of the Community Foundation of Sarasota County, remains blown away both by the level of generosity in a time of financial hardship and the instinctive reprioritization donors made with their gifts this year. The food bank always receives support in the Challenge. “Last year All Faiths did great, but they received about $180,000,” she said. “It just shows our community understands we have got to take care

of each other’s basic needs.”

The round-the-clock news coverage of the pandemic and the particular challenges around hunger surely fed the interest, Jerde said, and she credits local media for publicizing the needs of food banks and services, and national images of food lines forming in major cities earned play around the same time as the Challenge. Marketing by the organizations played a role. Holding a drive for donations during times of financial hardship brings with it the potential for disappointment. Jerde remained humbled by the way Sarasota’s fortunate continues to rally around those most in need.

“We can’t underestimate the unifying feeling that occurred through this Giving Challenge,” she said. “I’m still overwhelmed at what happened and with what this lifeline means to so many of our nonprofits.”

Foubister said in the absence of major food drives, individuals have eagerly stepped up to help the Feed Venice initiative directly. Volunteers have shown up to work in parking lots for Christian schools, sorting goods at workstations six-feet apart. While the number of people humbled enough to ask for assistance feeding their families has grown tremendously, so too have the ranks of individuals compelled to lend a helping hand. “It’s heartwarming to someone like myself,” he said. “We’ve had to turn three dozen volunteers away.” But there’s plenty of work to be done in the region. “The community of nonprofits is not a competition,” Foubister said. “We’re just a bunch of people who care.” Meanwhile, Sandra Frank said the All Faith’s Food Bank has seen a 120-percent increase in the amount of food given out over the course of the year, about 2.2 million pounds at last count, despite the breaks in the typical supply chains. But it hasn’t stopped workers from soldiering ahead, handling the increased workload and driven by the need they see. The lines to food distribution today can appear like they once did at theme parks, but that shows the value a food bank brings to the region in times of greatest need.

“We have a deep responsibility to our communities,” she said, “and we couldn’t let these people down.” SRQ