“It’s kind of an interesting and exciting time,” says John Bryant, architect and principal for Sweet Sparkman Architecture and Interiors. “Well,” he adds,” I don’t know if ‘exciting’ is the right word.” Bryant, a local expert in coastal design and architectural resiliency, has contributed to projects like The Bay, the Lovers Key State Park welcome center and Siesta Key’s main beachside park pavilions. The maybe-not-so-exciting time he refers to is the current environmental moment, populated with BBC nature documentaries, (un)natural disasters, a race against extinction and a world’s confidence in one Swedish teenager (who, calm yet panicked amidst climate anxiety, faces it nonetheless). But, while it may be tempting to sweep all of these environmental challenges to the side, on a local scale, Sarasota has been presented with questions and challenges that require immediate answers and solutions. By the end of the century—far enough away to live comfortably in denial but close enough that today’s middle schoolers will witness the change—Sarasota is conservatively projected to endure 1.5 feet of sea level rise. But the more painful truth could be as high as 4.5 feet which, in a coastal city like ours, will be an infrastructure game changer. “We’re probably not at the same spot as Miami is in terms of needing to do it yesterday,” says Bryant. “But we need to be doing it today.”

With many of Sarasota’s largest construction projects underway, like the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens master plan and the redefining of downtown Sarasota with The Bay project, today’s organizations with plans to advance are simultaneously faced with another challenge: to adapt. And yet, thinking environmentally and designing sustainably are no longer at odds with visitor experience or the beauty of new design. And, rather than keeping sustainable technology in the restricted areas of campuses—hidden from view and off the radar of visitors—these two projects plan to present their environmental considerations front and center, not only as answers to the problem but also as opportunities to educate the public on how an uncertain future can be approached. “The more sustainable features you’re able to bring into a project—honestly, they increase the enjoyment of your visitors,” says Bryant. “The more sustainable you’re making the building, the more you’re integrating the building harmoniously with the environment.” And it is with that same harmony that Selby Gardens and The Bay move toward the future, designing conscientiously and responsibly, refusing to yield or compromise.

Selby Gardens

Sitting down with the team for Selby Gardens’ three-part master plan—including Chris Cianfaglione, the senior project manager; Richard Roark, a landscape architect and the master planner for the project; and Jennifer Rominiecki, Selby Gardens’ president and CEO—one truth became clear above all else: Selby will not hesitate to take on a challenge as large and looming as climate change.

“The whole resiliency issue is what drove this whole master plan from the beginning,” says Rominiecki. “We have the world’s best scientifically documented collection of orchids and bromeliads and, right now, they’re housed on the ground floor in a flood zone in aging infrastructure. So there was this core need to really preserve and protect the world’s best collections of their kind.” With the collision of vulnerability and threat, some might simply move to a new site—away from the immediate coastline—but the team agreed from the beginning that simply relocating inland would not guarantee safety. And nothing highlighted that more than Hurricane Irma in 2017 during the start of their planning process. “That was a big exclamation point,” says Rominiecki. “We thought, ‘We have to do this and we have to do this now!’”

The result? Living buildings for a living museum. In form, function and feeling, the new Selby Gardens campus will serve the day-to-day needs of any botanical garden while also incorporating sustainable design. Much of the new campus will be shifted to the current parking lot—the high ground. And, with the mapping out of sea level rise and FEMA flood zones, Selby is “future-proofing” the grounds, making plans to protect and preserve it for decades to come.

The addition of mangroves along the shore provide natural fishery habitats, prevent erosion and reduce storm surge. And, during this process, the rarest of Selby’s collections will be duplicated and shared with sister botanical gardens around the country for optimal protection. But, perhaps the most exciting feature of the new master plan will be its status and accomplishment as the first net positive botanical garden complex in the world. “You have your fast-moving crises and you have your slow-moving crises,” says Roark. “You have to worry about water flooding and you have to worry about more intense hurricanes. But you also have to worry about the resource of the water itself. We try to show how important it is.”

Using technology like solar power and a water filtration system that will divert rainwater through rain gardens—before entering a 250,000-gallon stormwater vault and cistern (all of which will be visible and traceable by visitors)—places Selby in an epic new category of resiliency and environmental design. And, even when functional sustainability has run out, Selby will still embrace fashionable environmentalism through biomimicry (the imitation of nature). The concrete, hurricane-proof garage will meld with vines, marrying the most manmade of buildings with natural life—like epiphytes hanging from the ceilings in candelabra-fashion.

“It’s really easy here in Sarasota, and in coastal environments, to get hung up on resiliency meaning sea level rise and storms. But it really is multifaceted,” says Cianfaglione, who handles the site, civil engineering and city commission approval as the boots-on-the-ground local liaison for design teams. “It’s not just about a theory of trying to do the right thing. This has real value, and real value of land loss if they don’t start to do the right thing right now. This project looked at every opportunity to do the right thing. And, at every turn, the right, environmentally focused, sustainable design choice was made.”

Roark adds, “telling [Selby’s] story of adaptation is so important as a model for Sarasota.” The sustainable design and environmental approach to the new master plan won’t be hidden away but rather put on display for both the celebration and preservation of nature. It is also a continuing branch of education for the local botanical treasure, proving not just what should be done to face the future head on but what boundaries can be surpassed by interpreting challenges as opportunities for innovation and creative solutions.

The Bay

From the beginning, honoring, respecting and restoring the environment has been a central initiative for The Bay—not just a suggestion, according to Bill Waddill, the project’s chief implementation officer. With the goal to open completely within the next nine years, The Bay—in combination with the City of Sarasota, and both the private and public sector—will transform a 53-acre coastline into a blue and green oasis and park.

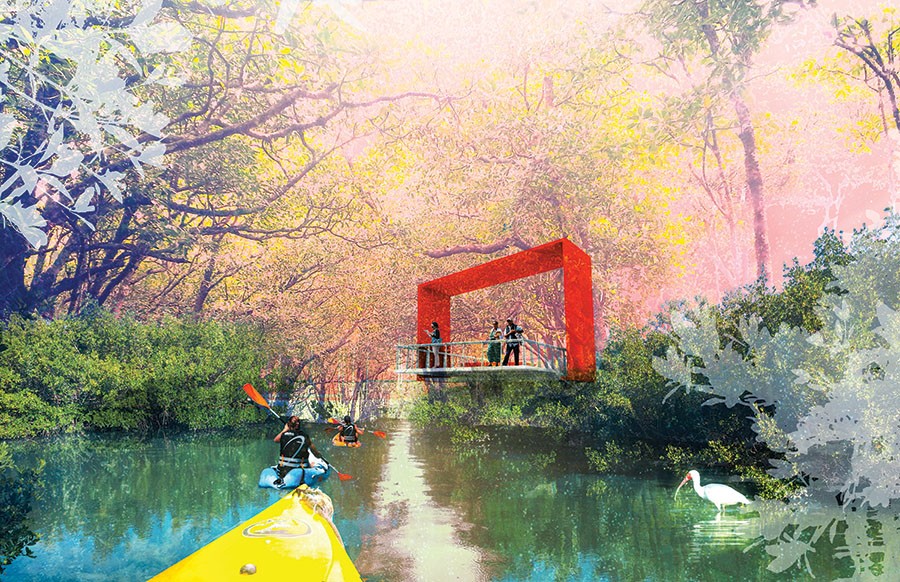

Acting as a lush foyer into Sarasota’s waterfront, The Bay will introduce kayak launches, reading gardens, scenic overlooks, a sunset boardwalk, mangrove walkways and a resilient ecological shoreline—forging an immediate immersion between residents and nature. But, more than that, The Bay faces the responsibility of mitigating potential environmental destruction and preserving the coastline, in a way that requires more than increasing tourism.

“We spent almost as much under the ground on water quality as we were spending on top of the ground,” says Waddill. With the site currently existing at about two-thirds parking lot, The Bay team has learned that about 70 million gallons of untreated stormwater currently flows directly into the bay—along with every drop of oil, littered plastic cup and forgotten facemask (much of it from U.S. 41, located a quarter-mile away).

Because of the decades-old infrastructure, which was designed and implemented prior to the Clean Water Act, a high-class filtration system that addressed the many faces of water pollution was in high demand. “So, what we decided to do is when we had the patient open for heart surgery, we needed to go ahead and fix the kidneys as well,” says Waddill. Deemed The Treatment Train, a combination of filtration implementations will treat runoff and stormwater before they rejoin the bay.

Bioswales—depressed marsh areas populated with soil and native plants—naturally treat the pollutants, which are then absorbed into groundwater while adding a bit of green to the more concrete areas. A No Mow Zone along stretches of waterfront sidewalks will remove the potential of grass clippings and fertilizer being discarded into the bay, while celebrating the natural Florida flora that was born for the job.

But the most innovative stop on The Treatment Train will be the Denitrification Trench—a six-foot-deep and six-foot-wide trench filled with a carbon-rich charcoal called biochar, which will neutralize the nitrogen in the stormwater for a 600-foot-long stretch. And, throughout the whole process, Mote Marine will test the quality of the water—comparing the baseline existing data with that of the treated water, actively gauging the effects and seeing how the biology might heal itself.

Then, to combat the more extreme threats like tropical storms and hurricanes, the construction site divides into a strategic east and west end. New construction, like the new performing arts center, will be designed on higher ground east of the shoreline—up and out of the floodplain about 14-and-a-half-feet, making the newest and strongest construction even more resilient to rising sea levels and storm surge. In contrast, the western third of the shoreline will be intentionally floodable--allowing feet of storm surge and flood waters to rise, inundate and recede, requiring little more than a cleanup and the potential replacement of lost plants. “That’s something that more and more parks around the country are starting to think about, is how can you incorporate resiliency into your design?” observes Waddill.

But, even more than the established practices of coastal design in the modern day, The Bay will be more than just a converted park with sustainable considerations. “What we realized as we’ve gotten into this project is that there was even more of an environmental restoration opportunity than we imagined,” says Waddill. Above ground, The Bay has taken on the expensive and timely challenge of preserving the trees (some older than 50 years) that have long resided along the coast—relocating almost all of them to preserve the already established 50-foot shaded canopy so that visitors can walk in shady comfort. “It was a substantial amount of time and cost to prepare them and then move them into place (around $35,000 per preserved tree), but we’re very proud of that and we thought it was the right thing to do,” says Waddill. In addition, the park will plant more than 1,000 new trees onsite, creating a lush oasis that introduces new fauna and continues melding nature with construction.

“I walk around and talk to people, and the environmental restoration resonates almost as much with some people as the park does,” says Waddill. “They love to come down and walk around, enjoy the shady environment and walk in nature, and that’s terrific. But it’s amazing how strong the environmental restoration is resonating with those in our community.”

In response to that passion, the sustainable design for The Bay will be obvious. There will be signage about the basics of the environmental decisions, as well as QR codes that lead to online deeper dives explaining what was decided, what was done and potentially what people can do at home to continue the same sustainable practices. Mote Marine will continue the education with first-grade students in Sarasota County and at The Bay visitor center. Families can also visit the new park and check out nature kits to engage more deeply with the environment, cataloguing what they see and where they can explore.

“Everything is really related,” says Waddill—the visitor experience, the science, the design and the natural world. No longer do environmental considerations or sustainable ideas need to simply be a box checked or an ugly addition hidden from view. Instead, sustainable design is the way of the future, preserving and supporting the environment so that it can be enjoyed and experienced for generations to come. SRQ