THIS YEAR MARKS THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE founding of Sarasota’s very own Circus Arts Conservatory, an institution with one foot in a historic past and both eyes set firmly on an ambitious future. Twenty-five years ago, Dolly Jacobs and Pedro Reis joined forces in an effort marked by a shared artistic passion and translated through a high-flying romance. In an interview with SRQ Magazine’s Executive Publisher Wes Roberts, Dolly and Pedro reminisce about how they found the circus, how they found each other and how their innovative approach to education has reinvigorated an appreciation for the circus arts within our community and internationally. For a town that in many ways was built by the circus through John and Mable Ringling, there couldn’t be a more exciting torch for these two innovators to carry forward.

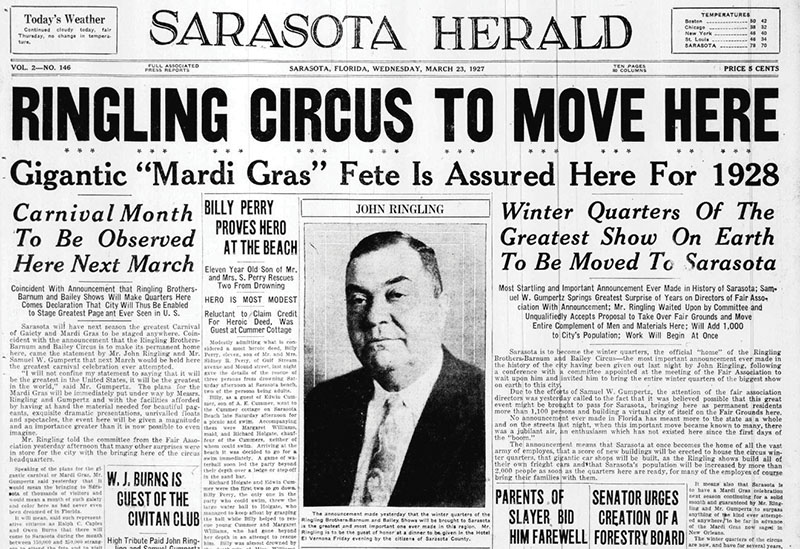

Twenty-five years ago, could you have imagined that this is where you would be? FOUNDER AND CEO PEDRO REIS: We were passionate about the idea of bringing back the living circus and conserving and continuing the legacy of the circus in Sarasota—the history that started in 1927 when the Ringling family brought their winter quarters to Sarasota. It’s just fantastic to be where we are today. The answer is no. We could not have imagined the amount of programs that we have today, the amount of outreach in the community, the amount of support we have from the community and from our donors and supporters. It’s just unbelievable. You start aiming in one direction, and then the journey goes left, right, zigzag, up, down, sideways and inside out, and you end up being in a different place that you didn’t expect. It has been an amazing 25-year journey.

With this model you have developed, could there be a circus in every large town in America? REIS: In 2017 we partnered with the Smithsonian. Our big top was actually on the National Mall. We learned that there actually is a circus school in every single state of the United States. When I came to America in 1984, there were three or four schools total. Circus has become cool. It’s diverse, it’s athleticism, it’s fitness, it’s all of the above. And of course we used the word “arts” [in our name]. There was a preconceived perception–the circus was connected in people’s minds to the carnival and to the freak show. There was the bearded lady, the sword swallower—that was a P.T. Barnum thing—and a focus on profit above all. For Dolly and me, it’s not about the money, it’s about the legacy, and how we can express our true art form so that the public will see, recognize and appreciate it.

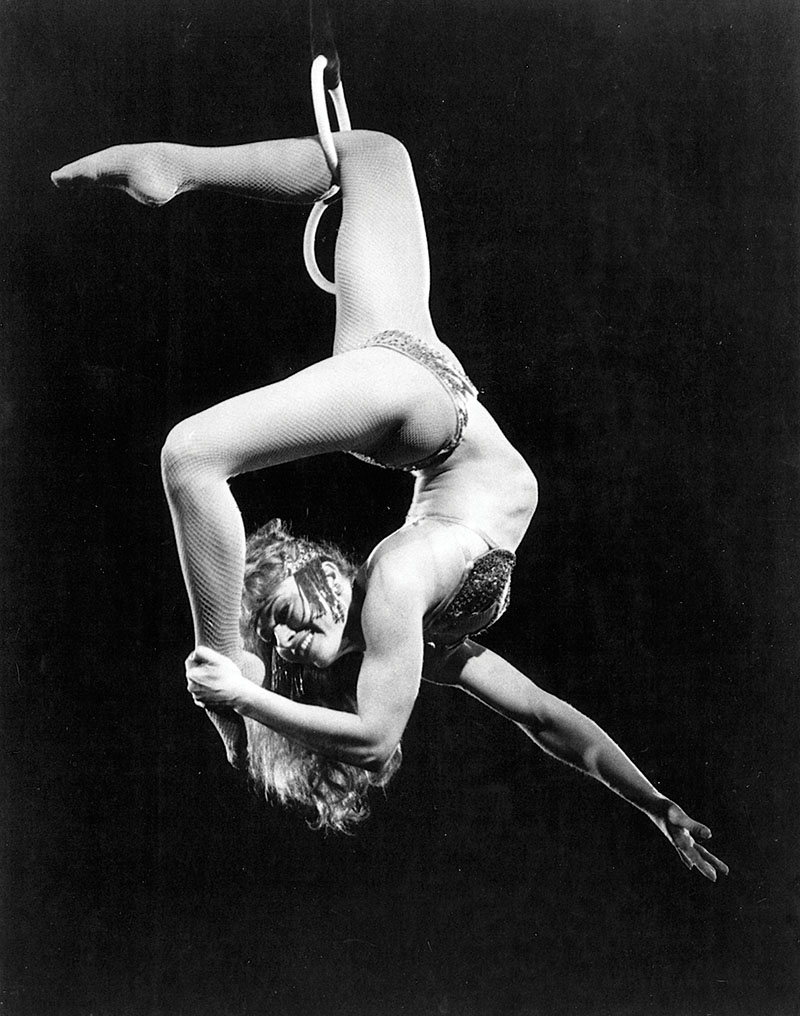

Dolly, you’re a true Sarasota native. So you were born in Sarasota, but you were also born into the circus. What does that mean to be born into the circus? CO-FOUNDER AND ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR DOLLY JACOBS: I don’t know a different childhood. I feel I have had the best of both worlds because I grew up here and was part of the community, part of Sailor Circus, part of the Sarasota swim team at the YMCA, but I also was able to travel with the circus at a young age. I’m very fortunate to have been born into the circus—the circus is a unique family. It doesn’t matter what country you’re from, what language you speak or what color you are, there’s a unity and a support for each other and a universal language.

I imagine part of that camaraderie comes from the famous phrase, which must be universal across performing arts, “The show must go on”, combined with the incredible trust that you are required to have in your fellow performers. JACOBS: It’s all the work that’s involved in getting to where you are in this world we call the circus—all that it takes to become a circus artist. We’re all across the world. We’re all involved. We have that common bond where you work with somebody maybe in Stuttgart, Germany or somewhere, and then you see them 25 years down the road and you reconnect like it was yesterday. You share the training, the skills, the dedication and the work ethic. It’s not an easy life, but you get a lot of self pride out of it. And just speaking for the women that raise their children, do the acts, drive the trucks, put up their rigging, fix the costumes, make dinner, everything that a housewife would do, plus perform.

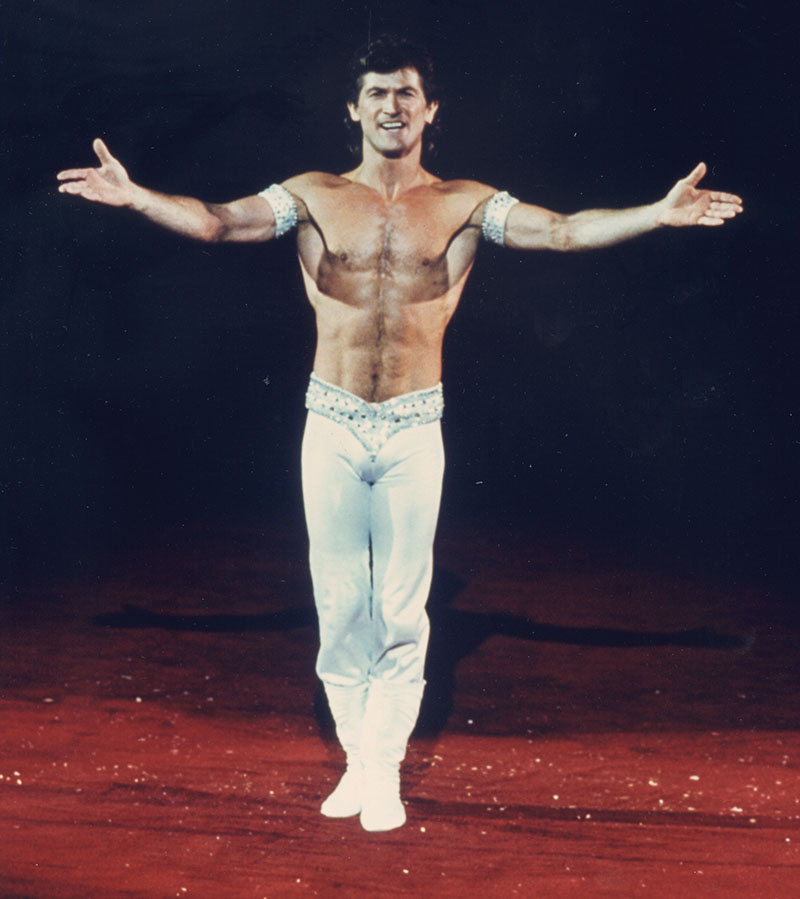

Pedro, you were not born into the circus, but somehow you were born with an irresistible draw towards the circus, right? REIS: My parents moved from one suburb to another in South Africa, and lo and behold, one morning, I woke up, went out of the house and across the street at the YMCA, I found out there was flying trapeze rigging and a trampoline. Wow, I got into lots of trouble sneaking through the fence at night and being chased around the trampoline by the warden. But it was like a magnet. There were a lot of young teenagers actually training to become professional trapeze artists. I befriended them and I would be the runner to go up to the shop and get a Coca-Cola or whatever they needed. They allowed me to go up on the flying trapeze. I just took one swing and said, “Wow!” I learned that this could become a vocation, a way of life. I realized that I could get to see the world by doing flying trapeze in the circus. In my 12th year of education at public school at Observatory Boys High School, three months into the final year, I just couldn’t take it anymore. I just actually took my books, got up out of the classroom, and said, “Excuse me, I’m leaving now.” I went down to the principal’s office and said, “Sorry, sir. I won’t be needing the books anymore. I’m joining the circus.” I walked out of the school and never looked back. I mean, the education that circus has given me, the culture, it’s just amazing, just totally amazing. And like Dolly said, it’s not easy. It’s hard physical work, but it’s very, very rewarding.

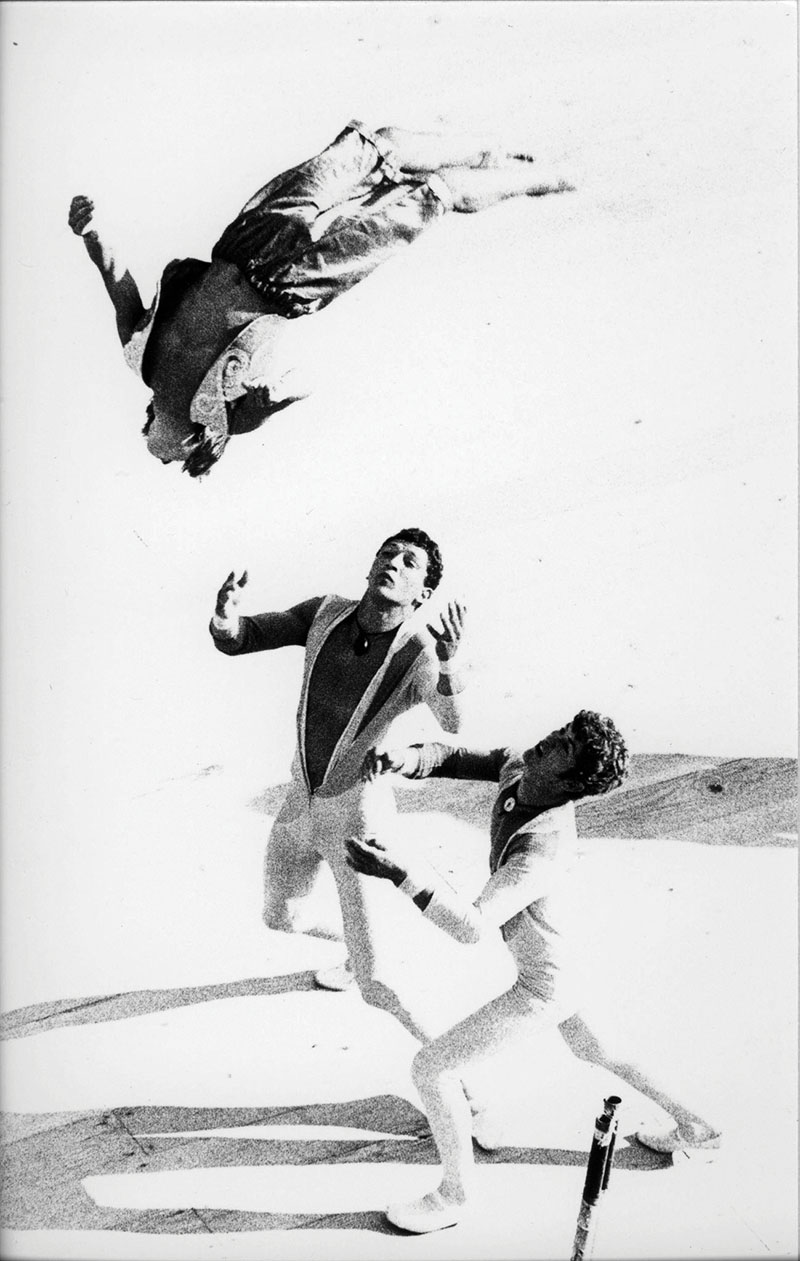

What is the draw? The feeling of flying, or the audience, or something else? REIS: There was no audience that first time. I was thinking, “Can I actually do a somersault to this person on the other side, catch it, swing, and then come back to the trapeze bar and land back on a pedestal.” That’s an accomplishment. And so then it’s increasing levels of discipline; single somersault, layout somersault, full-twisting somersault, double somersault, double forward somersault, triple somersault, double cutaway half somersault and then a double full. It’s you that you are building. And, I’m doing something that not many other people on this earth can do—something that not many people would even dream of doing because it’s so dangerous.

Are you a thrill-seeker in other areas? REIS: Not really. I’m not so much a thrill seeker, but instead a “unique seeker.” Dolly and I are total opposites in this area in general life. But when we are in the air, we both are asking, “What can we do that’s unique?” That’s really our signature. JACOBS: It sets you apart. Challenge yourself, push yourself, be the best at what you’re doing. It’s that drive that we both have.

Is it the highest accolade when someone who’s another flier compliments the performance? JACOBS: Oh, absolutely. REIS: I remember when I came to America in 1984. There was an organization, Showfolks, which was a social club for the circus membership in industry. It included all my childhood flying trapeze heroes—and many of them lived in Sarasota. So coming here to join Ringling was a dream come true. We were training in the Venice Winter quarters, and the Showfolks Club had a fundraiser. Afterwards, I was standing inside at the bar and this gentleman came up to me and said, “Hey kid, you got one hell of an act. My name’s Fay Alexander.” I was almost stuttering. The Fay Alexander!?! He was the guy that did the triple somersault in the movie Trapeze, in Paris at the Bouglione winter quarters.

I’m not sure how many people in Sarasota today know how common it was for circus people to come here to retire. JACOBS: My father Lou Jacobs came here from Germany in 1923. He worked in vaudeville for a couple of years. His brother lived in New York, and then he joined Ringling in 1925. I believe he lived with the [Flying] Wallendas on Arlington Street, where they had their home. The circus people did help build Sarasota. St. Martha’s Church was fundraised by the circus artists. John and Mable Ringling themselves; Ringling Bridge, Ringling Boulevard and Ringling Museum. Circus artists from around the world know of Sarasota, Florida as the home of the circus.

Pedro, originally you were at The National Circus School of Performing Arts. What was the first time your journey went “left, right, zigzag” as you said? REIS: Well, I started exploring how to run a non-for-profit, how to write a grant and how to raise funds. Different from flying on a trapeze. REIS: Totally different. And very, very soon into the enterprise, we realized we got the cart before the horse. I said, “We know circus. We know how to perform, but education, in the sense of curriculum and being accepted in the educational system, we don’t.” I thought it was going to take a really, really long time to learn it all. Two of our most wonderful supporters, innovators and educators were Syd and Rita Adler. They helped us broaden our educational horizon and vision and they helped us find our first big top— a Russian tent that was basically abandoned in Orlando. We found the creditors, we borrowed as much money as we could from Sarasota Bank, thank you, [bank president] Christine Jennings, for providing the loan, and we went and we bought this tent. Now where are you going to set up the tent? Ray Pilon was then county commissioner and he loved the idea of the circus. He helped us find the landowner, John Meshad, an attorney. John allowed us to put our big top on his property at no cost. We put the tent up and we believed “if we build it, they will come.” We both laugh now because we were so naive in that sense. We imagined people would see this big tent, and they’d just show up. It wasn’t that easy. We struggled. There was pain, but it’s just that our passion was so strong that we couldn’t fail, we just couldn’t. We weren’t making any money. Dolly actually got a contract to go to Busch Gardens. She worked there for three months to pay all the acts that worked for us in our circus. When you think back, you laugh about it and it was a true testament to endurance. Never give up. Just keep going and believe in your dreams and your passion. And 25 years later, guess what, we’re still here.

There must have been times where you really didn’t know if you could do it. JACOBS: We had a powerhouse show, incredible acts, because all of these artists who are friends of ours, believed in us and knew that we were going to present their art form at the highest level. And that’s what every artist wants. They don’t want to be upstaged by somebody barking to sell popcorn or souvenirs. And we did that. And having the support from the rest of our circus family really meant a lot to us. A lot of the artists cut their paycheck just so that they could help us get started. But sometimes we had more people in the show than we did in the audience. We didn’t have a lot of money for lighting and sound and all that. But the acts spoke for themselves and they were incredible top-notch performers and artists. From that very beginning, those people that came to see us, those that supported us, were blown away. Those were the stepping stones. Each year we got more people that saw the show, and if we could just get the people in the seats, we knew they would come back. REIS: We have volunteers that say, “I was with you from day one.” How amazing is that? As Dolly says, “You stand on the shoulders of those before you.” JACOBS: They gave us the foundation upon which we stand and it’s solid. Our mission and our goal is a hundred years down the road to ensure that it’s still going strong.

Working with the National Endowment for the Arts, Dolly’s Heritage Fellow recognition, setting up your tent on the National Lawn in D.C., these achievements all come back to an idea that started as a local commitment. REIS: In the beginning [our idea] was bringing back the living circus to Sarasota because this is where the circus needs to live. This is where the circus needs to express itself, and then be seen by the world. The circus world has evolved. There’s a lot more contemporary circus than traditional circus. You need to embrace it because life is evolution. When we present, it’s a mix of traditional and contemporary circus. Circus is a variety show. You can have live voice, you can have canned music, you can have a horse, you can have many horses, you can have someone on a violin, you can have someone on a tightrope and on the flying trapeze. It’s really encompassing so many different disciplines; dance, movement, ballet. But beyond that, being internationally recognized as a destination for the circus arts. Every year you have the International Circus Festival of Monte Carlo, in Monte Carlo, which this year will be held on January 19-28, 2024, and now, every February and March Sarasota is where you want to be to work as an artist.

Dolly and Pedro, at some point your two paths coincided, how did that happen? REIS: Well, first, I always knew of Dolly. I was always dreaming about going to America and dreaming about joining Ringling Brothers and looking at program books and obviously seeing the pictures in the program; Dolly Jacobs, Lou Jacobs, Gunther Gebel-Williams. This was my dream, right? So in 1983, I was in Switzerland, doing an act which we called “Cat’s Cradle”, where the catcher hangs by his knees in a frame and we, on top of the frame, leap into the air and the catcher comes out and catches you. You’re doing somersaults, pirouettes, hand to hand with no safety devices. I had been part of a troupe for four years when we decided to go different ways, and so I was thinking, “what am I going to do?” I heard about this act that didn’t exist anymore because it was too dangerous. People got killed. So I thought, “wow, that’s interesting.”

Oh no! That’s one way to find openings in the market! REIS: With my troupe, The Survivors, we went on to perform this act and after about a year, the [famous circus father and son team] Irvin Feld, and Kenneth Feld were scouting on behalf of Ringling Brothers. [They were told] to go see these crazy South Africans. A dream for us was always to go to Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus, [and here was our opportunity]. We signed the contract and came to Sarasota in December 1983 to train for the 1984, 1985 tour. It was New Years and we were at the Holiday Inn in Venice, celebrating, and in walked Dolly Jacobs.

And now we come to the love story. REIS: And so I said to my friend Mark David, “Can you introduce us?” Dolly had on blue denim jeans and a black leather jacket. I said, “Hi, my name’s Pedro.” And that’s when I found out her boyfriend at that time’s name was Pedro as well. Anyway, that was our first meeting.

It sounds to me you were equally fearless leaping for your catcher in the air as well as leaping for the ultimate golden ring as well. REIS: Absolutely. That was the first time we met. When I finished the tour, I was creating my new single act that I called the “Cloud Swing.” I went to practice at Sailor Circus, and lo and behold, who was practicing at Sailor Circus? Dolly Jacobs. So that’s when we kind of reconnected.

It seems to me that the month of July, 1990, must have been the best month and the worst month you ever had, right? REIS: Oh-yeah, July 4th very good, and then July 5th was not so good. JACOBS: 6th. It was two days later. We had been having a long distance romance. We were both featured aerialists and most circuses only had one featured aerialist. It was long distance, telephones and airplane flights to see each other. But in 1990, my father was already getting up there and I really needed time with him. I had been successful with all my work and I decided to stay home that year and take the year off. To stay busy I took up cosmetology. Pedro was with the Big Apple Circus. I took that opportunity to go up and visit him in New York And he popped the question. REIS: On the 4th of July, free fireworks!

This is the good part of the story. JACOBS: This is the good part. REIS: Yeah. I proposed, knowing there would be fireworks. JACOBS: And then two days later is when Pedro’s accident happened. Somebody didn’t set his rigging properly and he crushed both of his ankles. I was sitting in the audience watching. Nineteen screws and two plates, and that’s in the “good” ankle. I didn’t go back to Florida. I never finished my cosmetology degree. I stayed with Pedro as he recuperated in New York. Then rehab. And so the engagement went on for 17 years, the longest engagement in history. We finally got married in 2007 at the Ringling Museum and we had 250 of our nearest and dearest with us. His sisters came over from South Africa.

As a flier, I assume, this injury must have been mentally and emotionally crushing. REIS: I had my accident and recuperated. Then we came back to Sarasota. We went to the gym, we were at the gym every day, two, three hours. Dolly was very active and still had her act. Her sister and brother-in-law got a contract with Jimmy Hamid and John McConnell. They offered Dolly a contract for the same show. I don’t know what made me do it, but I picked up the phone and I called the producer, I said, “Hey, would you like to book my Cloud Swing act?” And he said, “I didn’t know you were doing your Cloud Swing act anymore.” I said, “Yeah, I’m back.” And he replied, “We’ll definitely book your Cloud Swing act.” So I hung up the phone and said to Dolly, “All right, I have to go and practice.”

And what was your reaction? JACOBS: I was surprised, but not totally surprised because I know his character. REIS: I got my rigging out and went to Sailor Circus and started practicing. Of course, the Cloud Swing is one thing, the tricks that you do, but the leap, that’s another thing because you completely let go of the rope. You’re flying through the air, you’re catching the rope 26 feet away. It’s pulled up on a single pulley, tied off with a piece of string. When you break that string, you’re dropping 25 feet to 30 feet before the bungee slows you down for you to touch the lightly lit floor and then, let go of the rope.

And this is what went wrong, originally? REIS: They pulled the rope up, tied the string and forgot to attach the bungee. Honestly, it’s a mind game. You play mind games with yourself and you have to talk your way through it—to trust yourself—to have the self-confidence to be able to do it—knowing that at any second something could go wrong. You know you can do it. So I did it. We did a short tour. We ended the season in Detroit, in the arena where the infamous Wallenda Pyramid accident happened. At the end of the tour, I literally took my rope, put it in a bag, closed the zipper and I was fine. Closure. I had total closure. I kind of say “passion is a flame and it’s okay for you to blow out the flame, but nobody else can blow the flame out for you.” And for me, it was like I blew out the flame, the candle, and I was at peace. It’s hard to describe, but that’s exactly how I feel. And then the other door opened and I got an opportunity to create an act with Dolly. A Pas de Deux, the strap act, the aerial act, new adventures. But, it didn’t last very long. We are very different characters and in the air, it was all “I’m right, she’s wrong. I’m wrong, she’s right.” It just didn’t work out.

So this is a married couple squabbling in the air? JACOBS: With the microphones off, it was a love story. But if we had had microphones on, it would’ve been a comedy act. REIS: And so I said to Dolly, “I’m going to find you a partner and enter Yuri Rjkov. “Yuri, how would you like to de-stress my wife?”

So now you are behind the scenes, sort of, while Dolly is in the spotlight? REIS: With the aerial Pas de Deux with Dolly and partners, I’m running the winch motor and I’m taking them up into the air. I must fly them around, and land them with precision. I mean, they have to land exactly at the right moment. You could break your feet or break your ankles. In my span of being an artist, an aerialist, I personally know how serious safety is. Knowing what can go wrong, will go wrong unless you take precautions. I look at everything. And everybody knows that about me. We had Alan Silva, who is an aerialist and does flying silks. His routine is pretty complicated. He flies way out and then from a dizzy height, 25 feet in the air, 30 feet away, and he swings down and lands in a split. The winch operator: you’re controlling that descent and that landing and there’s no room for error. That comes with dedication and experience. And taking it very seriously. It’s not flippant. You can’t be flippant about somebody flying in the air and landing on the ground. Do I feel very responsible? Yes. Am I haunted by it? No. I’m pretty at ease, because I know I can do it. JACOBS: Which put me at ease. When I was flying and he was on the winch, whether I did a solo routine or with a partner, I had total trust in Pedro. We’re human and there’s always an error. One time I was doing a solo routine in the summer program at the Ringling Museum. Beyond our control, the electricity and the sound, the lighting, everything went out while I was up there flying around. But I knew Pedro was on the winch, he was able to lower me in the dark. REIS: Manually without the power. JACOBS: And the whole audience was frozen, and Pedro says, “You okay?” And I landed on the ground and I said, “Yep, I’m fine.” Because he was on the winch. Confidence is such a key to aerial work. If you don’t have that confidence and fear comes in, then you shouldn’t be up there. If you start thinking about what can go wrong or what might go wrong and envision it, your body will follow. That’s whey when I teach, I try to tell the girls that they must always envision doing it right, you have to have that confidence.

Your acts are deeply personal, they’re very much a personal creation. JACOBS: It’s like artwork. You create this art. Before I did the straps, I was on the Roman rings. When I met Pedro, I was already doing this somersault from the rings to a rope. Pedro had me change it to put the rope further away. Pushing the limits. REIS: I have to get some insurance. Now we know what happened to that other Pedro. REIS: Still a very good friend of mine, as it happens. JACOBS: In all honesty though, the way I was doing the somersault at the time, it was so fast and so close, there was no room for error. Whereas putting it further away, then I could use my experience from the flying trapeze where you’re letting go and catching–I have more time to see where I’m going, even with the blind spot that comes with you turning. With Pedro being at the bottom of the rope holding that rope, I had confidence in him. And without that confidence, I don’t know if I could have done it. There was a time at Busch Gardens when I was doing it, and my hand slipped off. I came down. The rope went under my arm and took all the skin off. Pedro was standing there, I landed in his arms with my toes pointed. Thank you very much. The audience thought it was part of the act. He pushed me out there, gave me a kiss, said, “Take your bow.” REIS: Just smile. Keep smiling. She fell, she came down like 20 feet. And I just caught her. Possibly more. She fell down and I just caught her. I said, “Smile, keep smiling, it’s part of the show.” We keep going, the show must go on. JACOBS: Meanwhile, all the skin’s off. And then even the emcee didn’t realize it was a mistake. He sent me back for a second bow. REIS: And that’s when she decided to marry me.

What Dolly’s telling me is that you pushed her act further and further. JACOBS: Let me tell you what else he encouraged me to do. While his feet were still in braces recuperating from the accident, I got a phone call from the Nock family who do aerial. They are an incredible, historical family. And one of the family has a helicopter, and the brothers hang underneath the helicopter. One brother couldn’t do it, and called and asked if I would do the trapeze under the helicopter. He needed to know by the next day. I laughed because there was no way, but Pedro looked at me and he said, “Well, I would do it.” So he challenged me. So I agreed and I broke out in hives just thinking about it. And I’m at home on the rings, not on a trapeze. Luckily I took my rings and threw them in the trunk of the car, thank God I did that. There was no rehearsal. We flew over the lake once, with me inside the helicopter, and then the next time I was outside the helicopter holding onto my apparatus, and the helicopter goes up and pulls me away. No safety rope, no guidelines, nothing, no harness. I did it three shows a day for two weeks. REIS: Ten days. 30 shows. JACOBS: That was a feather in my cap. REIS: And it was winter. It was cold. JACOBS: There were 50 mile an hour winds one day. REIS: She went up 250 feet in the air hanging . . . JACOBS: Over a lake. And because I’d done competitive swimming and diving and lifesaving, I’m looking at the water, hanging upside down on the rings, imagining how I’m going to enter, what dive am I going to do. REIS: And you actually did do dislocates? [A dislocate is when the performer leaves contact with the apparatus so they are they unsuspended momentarily in the air, and then catches themselves.] JACOBS: I did end up doing dislocates. REIS: She actually started doing dislocates, full dislocates. And it was amazing. JACOBS: He dared me.

WHAT ARE YOUR PARTING THOUGHTS? JACOBS: With our lifespan, here on this earth, we are dedicating all of our time and energy to preserving this art form we call the circus. REIS: Circus is one of the oldest living performing arts. When you think about the cavemen, imagine they are dancing and doing things around the fire. A performance. If you look at the Egyptians, the art on the walls, you’ll see jugglers and acrobats. The circus has been around forever, and it evolves. It goes to a different level and different stratosphere. Now there is a lot more contemporary circus versus traditional. It’s very interesting to mix it all and to blend it all together. When I came to America in 1984 there were three circus schools, and now there are more than 300 circus schools. It’s exploding, it’s exciting, it’s happening. The circus is being recognized as being cool. [For the individual performer,] it’s about your body. It’s ‘how many balls can I juggle? 8, 10, 12, 15? What’s the record? I’m going to break the record. How many somersaults can you do? Oh, three. That’s the limit. Guess what, they’re doing four.’ That’s what circus does. Push the boundaries of the impossible. Make it possible. Make the impossible possible before your very eyes, and . . . smile.